Paris Journal 2013 – Barbara Joy Cooley Home: barbarajoycooley.com

Find me on Facebook 2012

Paris Journal ← Previous Next

→ Back to the Beginning

|

At the

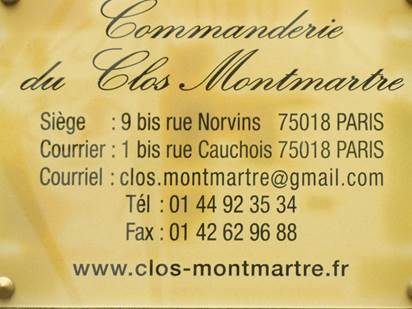

intersection of the rue Norvins and the Place du Tertre is a brass plaque

mounted on a wall next to a doorway.

The plaque indicates that this is the entrance to the “Commanderie du

Clos Montmartre.” It gives the wrong

URL for the organization’s web site.

The correct URL is www.clos-montmartre.com. The web site

tells us that this organization was created in 1983 by Maurice His, the

“President of the Republic of Montmartre,” with about thirteen or so of his

friends. The founding members wished,

because of their taste for wine, to be officially represent the vineyards of

Montmartre. Some 1901 law enabled the

creation of such a “confrerie vineuse,”

and these folks wanted one for the wines of Paris. Inside the

headquarters is a list of the founding members on a bronze plaque – behind

the bar, of course. Their leader is

called the Grand Master. A list of

successive Grand Masters is also on the interior plaque.

Not far from

this doorway to the Clos Montmartre (above) is one of the ubiquitous History of

Paris markers that we found to be even more interesting. It tells the story of the Folly of Sandrin. In 1774, Sir

Sandrin acquired, in the middle of the village of Montmartre, a property on

which he constructed a folly of a luxurious country home. It was sold to a wine merchant in 1795 and

then transformed into a clinic in 1806 by a Dr. Prost, a specialist in mental

illness. Dr. Prost was a disciple of

Dr. Philippe Pinel (1745-1826), who broke with the tradition of keeping the

mentally ill chained up in asylums.

Instead, Pinel (and Prost) experimented with new treatments that were

more “moral” and effective. They

believed that more gentle treatment that would inspire confidence in the care

being given, rather than add another layer of insanity. Only with this gentler care would the

mentally ill person be able to make the effort needed to improve his/her

state. There were

plenty of patients among the fatigued and depressed artists and writers of

Montmartre. Dr. Esprit Sylvestre

Blanche (1796-1852) took over the establishment in 1820. Along with his spouse, he tried to create a

family atmosphere for the patients.

One of them, Gerard de Nerval, said, “Here began for me what I call

the outpouring of a dream in real life.” Clearly,

doctors like Pinel, Prost, and Blanche paved the way for others like Jean

Martin Charcot (1825-1893), who are better known for their development of

more modern treatments for the mentally ill. Charcot, a

native Parisian, came from a modest background. His dad was a cartwright, or

wheelwright. Because of his success in

his studies, and with the support of his dad, Charcot was able to complete

the intern studies in the Hospitals of Paris, and finished them at the famous

(or infamous) Hôpital Salpetriere, where he started a neurology program. Along the way,

when he was 39, he met and married a rich widow, Augustine Victoire

Durvis. They lived a comfortable life

in a stately home at 217 boulevard Saint Germain, now the home of the Latin

American Institute. We have passed it

many times on our Parisian walks. (One of their

two kids was Jean Baptiste Charcot, a well-known polar explorer who named an

island in Antarctica for his dad the doctor.

Jean Baptiste married a granddaughter of Victor Hugo in 1896.) Among Charcot’s

students were Sigmund Freud, William James, and Georges Gilles de la

Tourette. It was Charcot who gave

Tourette’s syndrome its name, in honor of his student. It is

interesting to note that although we remember Charcot mostly for his work on

hysteria, he considered himself to be a neurologist and not a

psychiatrist. He also argued strongly

against the widely accepted notion that hysteria was rarely found in men. Charcot was

very upset that this prejudice caused many men to be misdiagnosed. He felt that hysteria could occur in the

most masculine of soldiers, and he thought that it was a condition that could

be caused by trauma. Thus, he was a

pioneer in the concept of diagnosing post-traumatic syndrome. One of

Charcot’s greatest accomplishments was that he was the first to describe

multiple sclerosis. He named it,

too. And he did important studies on

Parkinson’s disease. Tom wrote about

Charcot in his book, The

Ivory Leg in the Ebony Cabinet:

Madness, Race and Gender in Victorian America (University of

Massachusetts Press, 2001). He calls

Charcot “a towering figure” whose influence on William James, one of the

leading American philosophers of the 19th century (and

psychologist and physician), was significant. I’ll have to

remember to ask my nephew-in-law who is a neurological scientist what he

thinks of Charcot. Speaking of

family, I’m delighted that one of my nieces is taking up the study of French

in high school, and that she (and hopefully her mom) will be coming to visit

us in Paris next year. Tom and I both

firmly believe that it is important to use the foreign language you learn

while you are still young. |

Thursday, August 29, 2013

“La

Delivrance,” a stained glass window in the church

of Saint-Pierre de Montmartre. Note

the broken chain. Below, more scenes

from the interior of this church.

|